Salvete, readers!

I was really grateful that I could include illustrations in The Way Home, as Greek mythology lends itself to visual story-telling. The nine lavish illustrations enrich the story and give the book a unique character. I’m telling a tale of gods and monsters and magic… Why would I not want to see that fill the page? It’s the next best thing to having my book adapted for film. And given that The Way Home is intended for both YA and adult readers, it also felt right to include illustrations. In the age of the graphic novel, visual literacy is more important than ever. I didn’t want the illustrations to simply complement the story, but to be an essential part of it.

Every illustration functions like a panel from a comic book. Some things are better conveyed visually than through prose, which meant that I could be sparer with exposition. For example, I felt more comfortable leaping into the action with the fall of Troy because this was the first thing readers saw:

The image of the Trojan horse at night, wreathed in flames, instantly tells readers everything they need to know about where we are in the story. I didn’t need to tell the reader about the horse because it was all there to see. At my editor’s suggestion, I even ended up changing the first chapter because the illustration made some of the description redundant.

One of the most powerful images in the story is actually from a moment which isn’t conveyed through prose at all, but occurs between chapters.

The illustrator Matt Wolf is an old friend of mine, a Queensland-based artist. What I love about his work is that it evokes the numinous, the mysterious and the epic. Check out Matt’s Instagram here! He has a great ability to conjure other worlds with his artwork, and when I discovered that I would be able to include illustrations in the Ashes of Olympus trilogy, I instantly knew he was the one for the project. Matt took the idea of handling it like a comic book with gusto, creating vivid, dramatic and startling images which bring the story to life.

It was a pleasure to collaborate with Matt, who was easy going, professional, and transparent in his communications. I suspect I was more involved in the process of creating the illustrations than most authors. Initially I gave him the synopsis along with a set of extracts from scenes which I thought would make for good illustrations. I also provided notes on character appearances and photographic reference materials for him to use as a starting point.

In choosing the reference materials, I decided to go with artefacts from the Hellenistic or Classical ages of Greece, rather than stick too closely to the bronze age. Not historically accurate, perhaps, but instantly recognisable. If readers can recognise certain icons, it makes the story that much more relatable. However, I tried to do so in a manner sympathetic to the past. For example, in the illustration below the warriors are kitted out in hoplite armour with Corinthian helmets, but their swords are taken straight from the Myceneans. A case of gleeful anachronism! You can get away with these things when you are writing fantasy.

Aeneas’s appearance is modelled upon that of Alexander the Great. Alexander’s look brings to mind the idea of kingship in antiquity, partly because so many subsequent monarchs emulated him. But given that Alexander so consciously styled himself to look like a Homeric hero, I thought it was acceptable.

From there, I was happy to let Matt run with it. I made the conscious decision to give him the space to make his own decisions. It isn’t easy to hand over the story to another creative person and let them play, but its worthwhile. Matt did consult me and provided me with running updates, but for the most part I let him tell the story his own way. Sometimes his interpretation does differ from the way I picture things, and that is a good thing. Sometimes when you let other people into your world, the result is better than you could have possibly imagined. The illustrations turned out so well, in fact, that my publisher printed the book on white paper rather than cream to maximise their effect.

Matt, mate, if you’re reading this (and I know you are!!) I just want you to know from the bottom of my heart how grateful I am for all of your efforts. You helped to define the book and it stands out from the crowd because of you.

And if you would like Matt to illustrate your work, he is available for commissions.

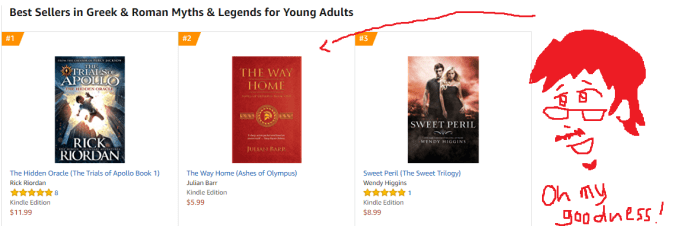

The Way Home is available via the online store of your choice!

Until next time,

Valete

PS. I’m offering a free short story exclusively to followers of my newsletter. Sign up here for your copy! Fear not, I won’t give away your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.